No, labradorite isn't a quartz but a distinct mineral called plagioclase feldspar. While both are silicate minerals, they differ completely in chemical composition, crystal structure, and optical properties - labradorite's signature iridescence can't occur in any quartz variety.

Picture yourself browsing a gem show when colorful flashes catch your eye at a miner's booth. "Is this iridescent stone some exotic quartz?" you wonder, holding a shimmering piece of labradorite while comparing it to a nearby quartz cluster shaped like hexagonal pencils. The seller sees your puzzled expression and explains why identifying minerals correctly matters more than appearance. Much like that moment of crystal confusion, this article organizes the science into a practical identification checklist. We'll walk through five key checks anyone can use - whether examining geological samples or choosing jewelry - to confidently distinguish these common yet distinct minerals.

Start by clarifying what labradorite fundamentally is - and isn't. Many assume all shiny crystals qualify as quartz, leading to misunderstandings in geology or jewelry valuation. This foundational understanding prevents misidentification when examining specimens.

Labradorite belongs to the plagioclase subgroup within the broader feldspar mineral group. Feldspars form the most common rock-forming minerals in Earth's crust, characterized by calcium and sodium aluminum silicates. In contrast, quartz forms independently as pure silicon dioxide crystals. One gemologist we interviewed shared how museums constantly re-label donated "rare quartz" pieces revealed to be misidentified labradorite once examined under polarized light.

The feldspar versus quartz confusion persists partly because both appear in similar environments, like glacial deposits. Technical analysis shows labradorite typically contains 50-70% calcium components in its solid solution series, differing chemically from other feldspars like orthoclase. When in doubt, check locality information since quartz commonly develops in hydrothermal veins while labradorite emerges in specific igneous complexes.

Moving beyond surface appearance, molecular architecture explains their distinct behaviors. Understanding these invisible differences helps predict physical properties and why cleaning methods vary for labradorite jewelry versus quartz pieces.

Quartz maintains a consistent SiO₂ framework that forms orderly helices, whereas labradorite incorporates sodium, calcium, and aluminum creating complex aluminosilicate sheets. This fundamental distinction means quartz lacks the elemental building blocks for labradorite's iridescence. A geology student recounted attempting quartz recrystallization experiments, only to realize labradorite's layered calcium-rich structure prevents similar processes.

X-ray diffraction reveals quartz's symmetrical trigonal pattern allows light to pass uniformly. Labradorite's triclinic crystal orientation creates irregular angles where light refracts across alternating mineral plates thinner than wavelengths of light. Industrial applications exploit this variance; quartz serves as oscillators in electronics due to stable vibration rates impossible in feldspar’s asymmetric structures.

When visual similarities cause uncertainty, physical properties become reliable identification tools. These measurable differences inform everything from jewelry durability to mineral treatment care.

Testing with common objects reveals quartz ranks approximately 7 on the Mohs scale compared to labradorite's 6-6.5 hardness. This difference means quartz maintains polish better over time. Jewelry designers note that labradorite pendants develop fine scratches from quartz-dust common in environments like beaches or construction sites – why protective settings prove necessary.

Quartz demonstrates conchoidal fractures resembling broken glass whereas labradorite cleaves parallel to two planes at 90-degree angles. Field researchers recall identifying eroded specimens in stream beds by labradorite's characteristic step-like cleavage patterns versus quartz's curved surfaces. Specific gravity subtly varies too; labradorite ranges 2.65-2.75 against quartz's consistent 2.65 density.

Light interactions provide the most striking identification clues. By understanding what creates each mineral's visual signature, you’ll recognize why their effects fundamentally differ despite superficial similarities.

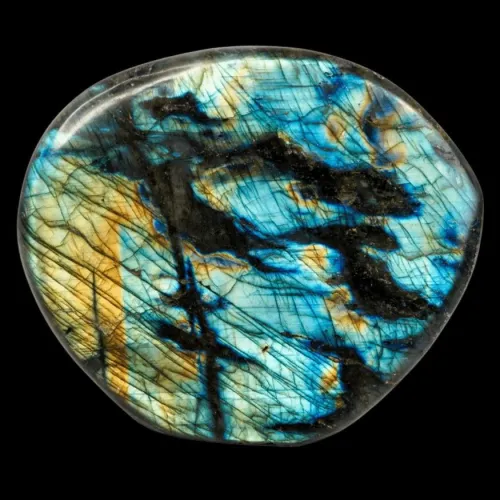

Labradorite's iridescence originates from light refracting between alternating mineral exsolution lamellae layers thinner than visible light. These microscopic structures diffract light consistently depending on viewing angle. Quartz may display rainbows from fractures but lacks the consistent layered structure essential for true labradorescence. Gem dealers demonstrate this by rotating specimens under a single light source; labradorite shifts through spectral colors while rainbow quartz displays fixed patterns unrelated to orientation.

Quartz typically exhibits vitreous luster even in rough form whereas labradorite shows glassy to pearly sheen particularly along cleavage surfaces. Transparency ranges differ significantly too – quartz readily occurs in transparent forms, while labradorite generally ranges from translucent to opaque except in thin slices. Light refraction tests confirm this: quartz refracts light at approximately 1.54-1.55 versus labradorite's higher 1.56-1.57 range detectable by refractometer.

Geological history leaves detectable fingerprints on mineral specimens. Origin awareness helps evaluate authenticity, value, and preservation requirements when examining potential quartz-labradorite confusion pieces.

Labradorite primarily forms in basaltic magmas with high calcium content that slowly cool to preserve its layered structure. Notable deposits emerge in specific volcanic complexes like those in Labrador, Canada and Madagascar. Conversely, quartz commonly develops in various contexts including volcanic environments, metamorphic rocks, and sedimentary deposits through hydrothermal activity and silica-rich solutions.

Post-formation weathering reveals another distinction; quartz withstands environmental exposure more effectively than labradorite. Field collectors note labradorite specimens display faster surface decomposition when exposed to acidic groundwater or coastal air. Long-term preservation involves storing minerals separately to prevent hardness-based damage since harder quartz can scratch labradorite during casual storage.

Transform what you've absorbed into actionable recall. Before purchasing mineral specimens or jewelry, pause to rehearse these distinctions – doing so turns abstract knowledge into practical confidence.

Recall labradorite's signature flash that changes with viewing angle - never seen in true quartz. Notice how quartz typically forms distinct hexagonal crystals unlike feldspar blocky shapes. Check hardness with available tools like pocket knives or glass plates whenever possible. When in doubt about mixed lots, ask about geological provenance since formation environments rarely overlap significantly.

Q: Can quartz and labradorite form together?

A: Technically yes, but not intergrown. They may occur in the same rock with quartz filling fractures in host rocks like basalt containing labradorite, appearing together but maintaining separate crystal structures.

Q: Why do some sellers mislabel labradorite as rainbow quartz?

A: Descriptive naming rather than mineralogical accuracy sells stones. While iridescent labradorite offers genuine labradorescence, "rainbow quartz" describes artificially treated or fractured quartz displaying surface colors without authentic mineral interactions.