Labradorite forms through slow crystallization in subsurface magma chambers over geological timescales, requiring precise temperature (600-900°C) and pressure conditions to develop its signature iridescence from microscopic light-diffracting structures within feldspar minerals.

Picture this: you're browsing an artisan jewelry stall when a pendant catches your eye - a seemingly ordinary gray stone suddenly explodes with electric blue flashes as you tilt it. "Labradorite magic!" the vendor smiles. But that momentary wonder sparks scientific curiosity: how does nature engineer such light shows within rocks? Instead of diving into academic papers, we'll unpack its formation through five observable bedrock principles. Consider this your field guide to decoding earth’s hidden artistry.

Start with a simple scene: A friend passes you a rough, unremarkable stone. "It’s labradorite," they say. Before dismissing it as dull, recall that its plain exterior hides transformative potential. Knowing its fundamental nature helps you appreciate why this happens. Labradorite belongs to the plagioclase feldspar family, characterized by its sodium-calcium aluminosilicate composition. This mineral doesn't appear randomly; it's deliberately crafted by Earth's igneous systems.

A friend of yours once visited volcanic regions where geothermal activity visibly transforms landscapes. These surface events hint at deeper processes. Labradorite originates when molten rock cools slowly in underground chambers, allowing atoms to arrange into orderly crystalline structures. Specifically, it forms in mafic igneous environments like basalt or gabbro, where iron-magnesium rich magma provides the necessary chemical ingredients. Think of this as Earth's crucible—high heat permitting molecular movement, and insulation enabling precise organization over millennia.

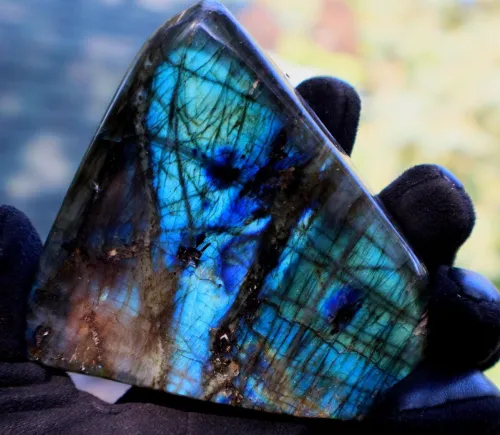

Notice a polished labradorite’s occasional milky opacity next to its flashes. This visual cue signals its feldspar lineage. Unlike single-crystal minerals, labradorite develops lamellae—alternating thin layers with slightly different compositions. These layers become the canvas for its optical performance. Crucially, its chemical structure features interlocking aluminum-silicon-oxygen tetrahedrons, creating a stable lattice where trace elements integrate without compromising integrity.

Imagine baking temperamental soufflé—it collapses if temperatures fluctuate. Similarly, viewing labradorite through formation's lens reveals why stable conditions matter. Its existence balances three interdependent environmental factors you can mentally map onto deep Earth environments.

Picture this scenario: magma cooling too rapidly creates volcanic glass without crystal growth; too slowly allows other minerals to dominate. Labradorite crystallizes specifically between 600-900°C (1112-1652°F). This temperature range permits sodium-calcium molecules to align while remaining fluid enough for layering. Outside this zone, different feldspars form. This explains why specific deposits—like those in Madagascar—display exceptional color play, having "baked" at optimal temperatures.

Visualize the immense weight of overlying rock pressing down on subsurface chambers, equivalent to dozens of atmospheres of pressure. This compression stabilizes the cooling environment, preventing sudden changes that fracture developing crystals. The uniform pressure allows microscopic layers in labradorite to stack with near-perfect alignment—critical for its eventual light show. Significant pressure shifts might instead produce non-iridescent minerals.

A friend once compared geological time to knitting complex lacework—each stitch deliberate but invisible daily. Labradorite's creation epitomizes slow craft. From liquid magma to iridescent stone, its evolution involves distinct stages observable in well-formed specimens.

Consider how dust particles seed raindrops in clouds. Similarly, microscopic imperfections in cooling magma become nucleation points where labradorite crystals first anchor. Tiny crystallites slowly grow radially, assimilating surrounding calcium, sodium, aluminum, and silicon ions. Over centuries, they expand until their edges meet adjacent crystals, forming the interlocking mass called crystalline rock. This slow-motion assembly allows atoms to fall into precise positions.

Notice how laminated pastry creates flaky texture through alternating dough-butter layers. In labradorite's case, slight chemical variations during crystallization create striations. As concentration gradients shift in the cooling melt, alternating bands of calcium-rich and sodium-rich feldspar develop parallel lamellae. These layers - sometimes thinner than light wavelengths - become the diffraction engines. Crucially, this process may span 50,000+ years, with growth rates measurable in millimeters per century.

Mantle rocks typically remain buried. Tectonic uplift over eons eventually brings labradorite-bearing formations near the surface. This exposure to weathering can leach iron from surrounding material, sometimes introducing reddish-brown surface staining that contrasts brilliantly with iridescent flashes. Such color dynamics only complete after extraction from the formation environment—where the real-world journey starts at quarries like those in Finland.

Recall that moment in the jewelry shop—turning the stone to reveal sudden blues and greens. That spectacle originates not from pigment but physics embedded during formation. Three technical conditions collaborate to produce the phenomenon.

Imagine sunlight hitting a DVD surface, breaking into rainbows. Similarly, light waves striking labradorite's microscopic lamellae bend and reflect internally. When light hits interfaces between differing feldspar layers, its waves interfere—some colors amplifying, others canceling. The resultant flashes depend on layer thickness and viewing angle. This selective reflection creates the signature "schiller effect," appearing metallic yet entirely mineral-created.

A single labradorite piece might show flashes ranging from cobalt blue to teal green. Trace elements introduced during growth—copper for blues, iron for gold-greens—absorb certain wavelengths, modifying reflected light. Interestingly, most colors stem from crystal structure rather than chemical dyeing, explaining labradorite's dynamic response to movement and why synthetic versions often fail to replicate this complexity.

A lapidarist polishing labradorite doesn’t create luster—they expose it. Natural fractures, weathering, and rough texture obscure internal architecture. Cutting parallel to lamellar planes slices open optical windows, while meticulous polishing minimizes surface scattering. Well-executed work optimizes light's path through these nano-layers. Without this alignment, as with incorrectly oriented slabs, stones may appear disappointingly matte.

Consider how archaeologists preserve context—where an artifact emerged often reveals its story. Similarly, labradorite's geographic settings hold clues to its formation history. Not all deposits develop equal visual drama.

Picture miners working Canada's remote coastlines: they retrieve labradorite through glacial deposits rather than active volcanoes. Formed originally in deep magma chambers 1.5 billion years ago, uplift and erosion eventually transported these minerals to accessible locations. Significant deposits require both favorable formation conditions and subsequent geological exposure—making sites like Madagascar's Andranondambo region historically productive. Volcanic eruptions sometimes eject surface specimens, explaining why Iceland beaches occasionally yield colorful fragments.

After eons underground, how does this mineral fare on your windowsill? With 6-6.5 Mohs hardness, it's sufficiently durable for daily handling. While acidic environments can etch its surface, normal exposure tends not to damage internal structure. Its specific gravity (2.68-2.72) makes it substantially dense, contributing to the satisfying heft of quality pieces in hand—like comparing paperback to leatherbound books.

When encountering labradorite next—whether in gallery cabinets or mounted in pendants—remember three cornerstones: Its layered anatomy forms when magma cools slowly beneath continents, precise thermal conditions enable color-producing structures, and skilled cutting unveils natural optics sealed in stone. Before buying, look beyond the flash: examine surface fractures that might compromise durability, assess transparency to indicate crystal integrity, and rotate pieces to authenticate structural iridescence versus surface treatments.

Q: Can volcanic eruptions create labradorite quickly?

Eruptions produce volcanic glass or tiny crystals because cooling occurs too rapidly. Significant labradorite formations develop deep underground where slow cooling permits layered growth over geological durations.

Q: Why does some labradorite show multiple colors while others display single hues?

The range depends on lamellae thickness variations within individual specimens. Stones from Finnish deposits often show vibrant spectral diversity because consistent formation conditions allowed more uniform layering.

Q: Are all iridescent stones formed like labradorite?

While structurally similar minerals exist (e.g., spectrolite), they form under comparable conditions with slight compositional differences. Synthetics may attempt replication via lab processes, but natural geological timescales remain impossible to duplicate.